Harvey W. Peace

Website

Navigation

Saw and File Manufacturing in Brooklyn in 1884

A bit of insight on the saw-making and file-making industries in Brooklyn in 1884. From The Civil, Political, Professional and Ecclesiastical History and Commercial Industrial Record of the County of Kings and the City of Brooklyn, N.Y. From 1683 to 1884.

SECTION VIII.

Saws and Files.

This is Mr. Frothingham's heading, and his statistics are: 24 establishments; 8161,900 capital; 302 hands; $97,647 wages; $90,718 material; $249,805 annual pro- duct. The census office assumed that there was but one saw manufacturer in Brooklyn (there were three at that time), remanded him to the miscellaneous industries, and inserted Files, 12 establishments, $25,750 capital, 76 hands, $29,192 wages, $21,910 material, $68,509 annual product. Both entries are hopelessly wrong, and only illustrate the folly of meddling with statistics, which the officials of the census office were incapable of understanding. The two branches of business, which are intimately connected, have been carried on with many vicissitudes, but the annual product of the two is not now less than $500,000, though there have been several failures within the last two years. The number of hands is probably now not far from 400.

But, as the processes of manufacture differ materially, and the saw manufacturer need not be, and often is not, a manufacturer of files, we will treat of saws first, and afterwards of file-making.

The manufacture of saws and files is not an old industry anywhere in this country. It is not yet fifty years since the English file manufacturers declared that the Yankees would never be able to acquire the art of making files; that the skill required had passed from generation to generation, and that no American could ever by any possibility acquire the sleight of hand necessary to cut files evenly and perfectly. It is about forty-five years since the manufacture commenced, and for more than a score of years past the American files have ranked as high as any of English or French manufacture.

The saw manufacture has passed through a similar experience. The Sheffield manufacturers thought they had reduced their business to a system and perfection which defied competition. The tempering, toothing, grinding and finishing a saw were each processes requiring long practice and training, and it was not to be supposed, for an instant, that a people who had had no experience in such a manufacture, could compete successfully with the English saw works and their skilled workmen. But stranger things than this have happened, and it has come to pass that, while we manufactured about $1,000,000 worth of saws in 1880, we imported in that year only $11,475 worth, and exported in the same year $37,271 worth, and about $11,000 of this to Great Britain and its colonies.

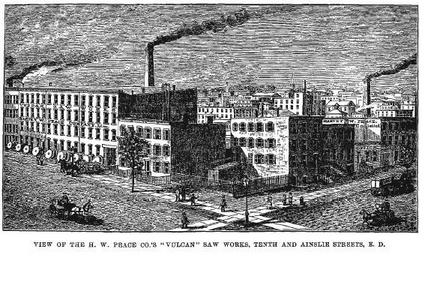

There are now, according to the census of 1880, 89 saw manufactories and 179 file works in the United States, and 18 of the former and 37 of the latter in the State of New York. We have no positive knowledge as to the first manufacturer of saws in this country, but among the earliest, as well as the largest, was the firm of R. Hoe & Co., who afterwards embarked so largely in the production of printing presses. The early saw and file manufacturers found it desirable to import skilled workmen, saw-makers, saw-grinders and saw- handlers from Sheffield, to train their apprentices and young workmen in the difficult processes of the manufacture; and in 1848 they invited a father and two sons by the name of Peace, experienced and skillful saw grinders, to come over and manage their saw- grinding department. They came, and their work gave ample satisfaction. The elder son remained with Messrs. Hoe for thirteen years, and in that time made himself completely master of all the processes of the trade, something very rarely attempted in that business. In 1861 the two brothers commenced business for them- selves, at first in small quarters in Centre street, New York; after a little, they removed to Johnstown, N. Y.; but in 1863 settled finally in their present location at Tenth and Ainslie streets, Brooklyn, E. D. Here they have, or a t least the older brother has, built up a fine business, the establishment being the largest, with one 3r possibly two exceptions, in the United States. Mr. Peace confined his industry to saws alone; but of these be makes every known variety.

The steel used is principally of Pittsburgh manufacture, and while its quality is excellent, Mr. Peace complains that two of his competitors, who manufacture their own steel, are enabled to use steel which costs them only about one-half the market value, while he is obliged to use steel purchased at the market price, and is thus handicapped at the very beginning of the race. Mr. Peace is a believer in a tariff with a fair degree of protection for manufactures, but he does not believe that it should be such a tariff as will discriminate against the manufacturer.

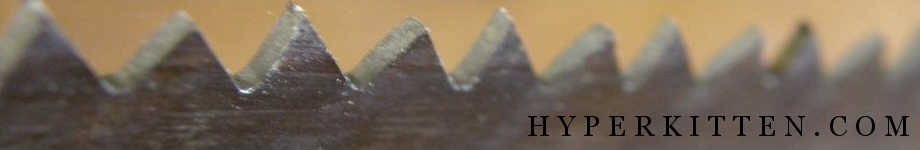

The steel used is rolled at the rolling mill to the proper length, width and thickness. The steel for carpenters' saws is in square sheets, which are divided diagonally, each sheet making two saws. Being cut into the de- sired shape, the future saws are toothed and filed while the steel is in the soft state. The teeth, which are of a great variety of forms, according to the purposes for which they are designed, are, except in the more complicated forms, cut by automatic machinery, the ma- chine for cutting the teeth of the carpenters' saws making 1,200 teeth per minute. The burr, or roughened edges, raised by shearing and toothing, are next knocked or rolled down. They are then hardened in oil, and tempered (a difficult and delicate process), a particular shade of color being required for the requisite temper. After the tempering, they go into the hands of the saw makers, to be hammered on an anvil as true as possible; they are then taken to the grinding shop, where each saw is ground for the purpose for which it is to be used. Most of the saws are ground on a machine, the saw passing between rollers to the grindstone, and passing out between other rollers on the other side. The jig and compass saws are ground by hand, the grindstones, in all cases, being driven by steam power.

The saws go next to the polishing shops, and, after polishing, are blocked (straightened by being hammered on a hardwood block), and, as the processes through which they have passed have somewhat impaired their elasticity, this is restored, if need be, by heating t o the required color. They are next set, filed, etched and oiled, when those saws which do not require handles are finished, ready for packing. The carpenters' and cross-cut saws are transferred to the saw-handler's department, and the blades are punched to receive the screws for the handles; and in one pattern, which is patented, a portion of the upper part of the blade is cut out by a die, and the handle fitted to match this exactly, and, like the other handles, is secured firmly in its place by screws. The handles are made of beech and apple wood principally, though mahogany, rose- wood, cherry, and black walnut are used to some extent.

The logs of these woods are first sawed into boards of the proper thickness, and then thoroughly steamed and dried. The handles are then marked out by pattern, and sawed out by band or jig sans, burred and filed into shape, smoothed by sandbelts and sandwheels, oiled and polished, and finally slit and bored ready to receive the blades.

In the manufacture of saws, the division of labor is carried to a remarkable extent, not in the production of different kinds of saws, as might be expected, but in the different processes required in the production of the saw. Each process is a trade by itself, and hardly ever does a mechanic pass from one to another. The usual divisions are saw-makers, saw- grinders, saw polishers and finishers, and saw-handlers; but even these are sub-divided; the man who hardens and tempers the saw has no knowledge of the processes of toothing and filing, nor of the smithing and hammering; so that there are three distinct trades under the head of saw-making; in saw grinding, the man who grinds the saws on a machine cannot be transferred to the work of grinding them by hand. In the polishing department, the polisher cannot do the setting, filing, retempering or etching. He might do the graining, which is effected by passing the polished and finished saw between hardwood rollers.

The saw-handlers have also several subdivisions. It is very rarely the case that a man has made himself a master of all the processes, as Mr. Harvey W. Peace has done, and is capable of superintending and directing each effectively. This is to be regretted, because it is a business which can only be conducted success- fully by a man who is thoroughly familiar with every department of it, and who has, at the same time, the executive ability needed in the buying and selling, and the financial management of a large business, and the power to control large bodies of men successfully. Without these qualifications, failure in the end is inevitable. There have been many sad examples of this in Brooklyn, and the successive disasters have left the Harvey W. Peace Company, Limited, practically alone in this industry, their only competitors now being some small shops which make only one or two descriptions of saws, and from their limited means, the quality even of these lacks uniformity.